Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

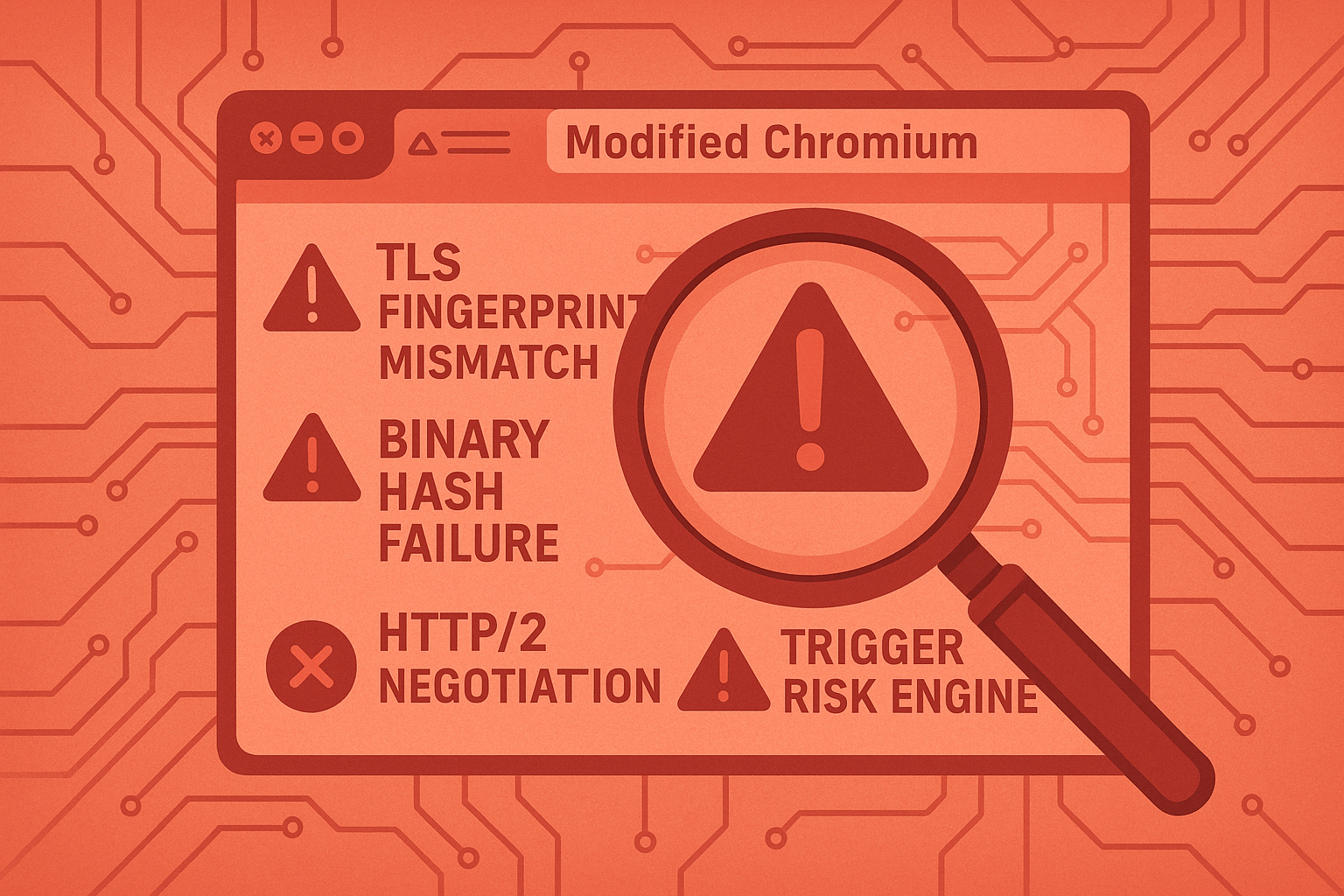

- Browser detection has shifted from JavaScript-based fingerprinting to transport-layer analysis (TLS, HTTP/2).

- Anti-detect browsers, which modify Chromium, often fail at this new layer of detection because their network signatures don’t match real browsers.

- The most effective approach is to use real, unmodified browsers and control the environment around them.

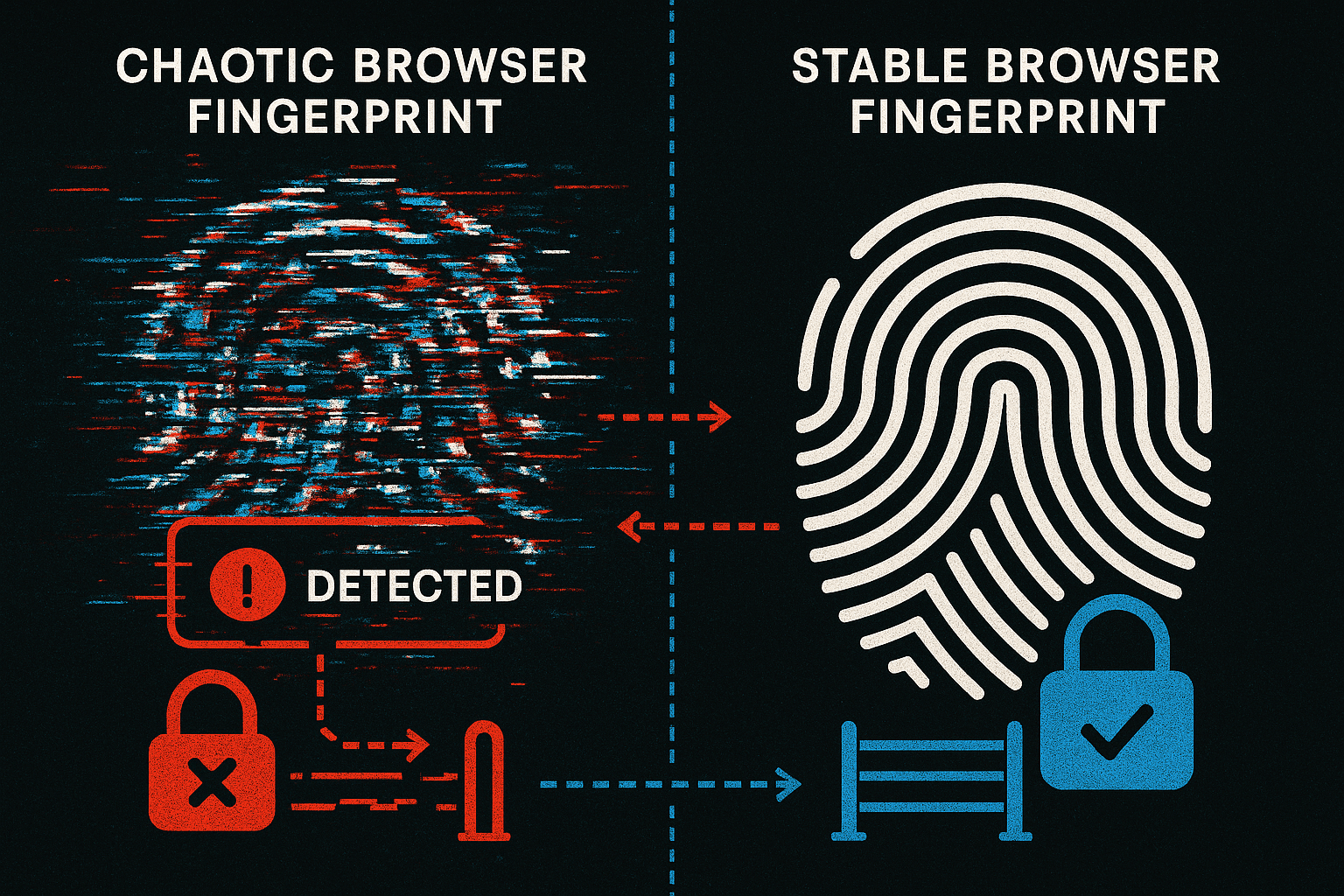

- Randomizing browser fingerprints is a red flag for detection systems, which look for consistency and normality.

How Did We Get Here? The Problem Nobody Can Explain

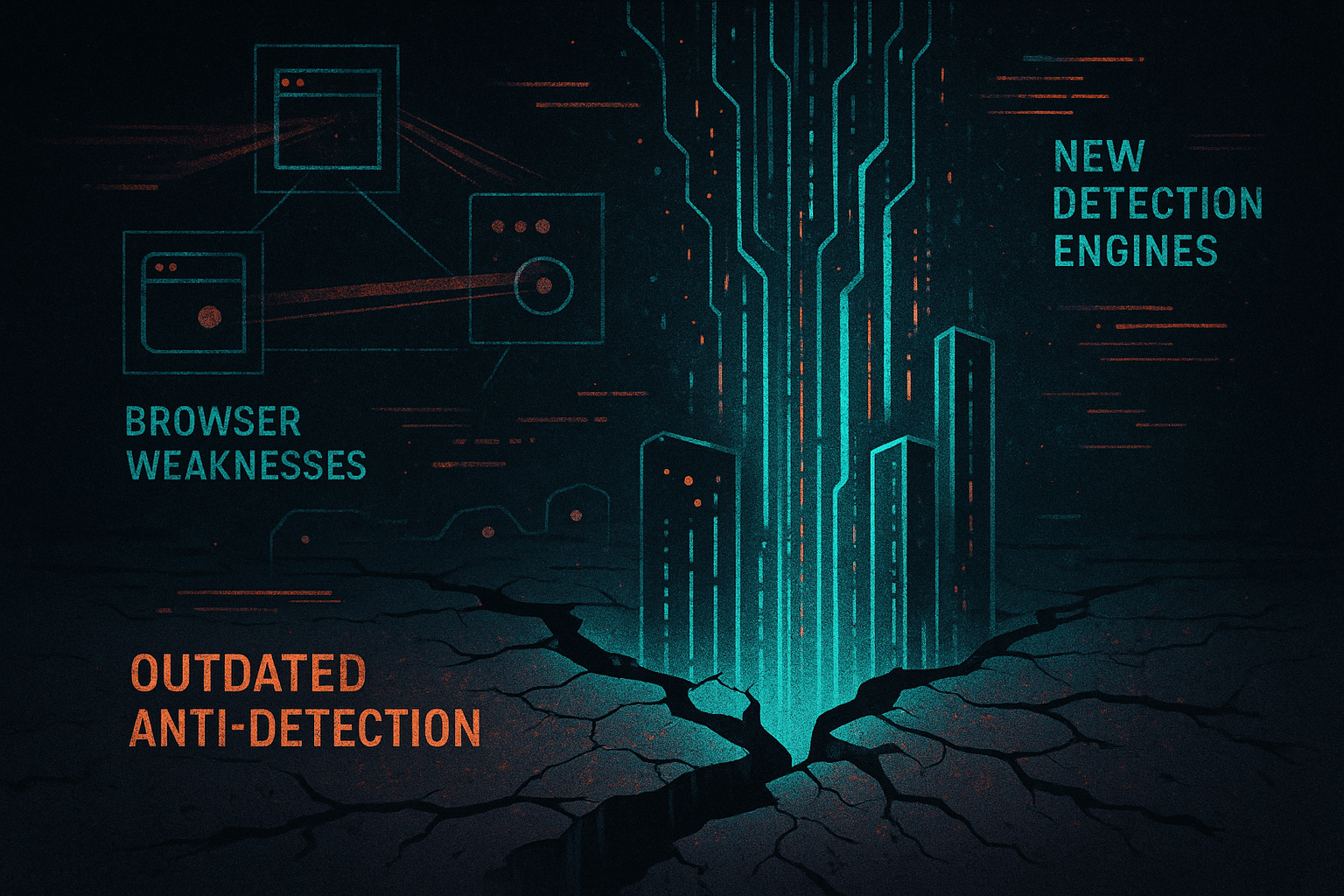

You’re not imagining it. The ground has shifted beneath your feet. You’re seeing more friction, more verification loops, and more “unusual activity” warnings. Your burn rates are climbing, and the methods that worked for years are suddenly failing. The common explanation is that “detection got smarter” or “platforms cracked down.” That’s true, but it’s not the whole story. The real issue is a fundamental, architectural mismatch between the tools many of us rely on and how detection actually works now. This isn’t a problem that a simple feature update can fix.

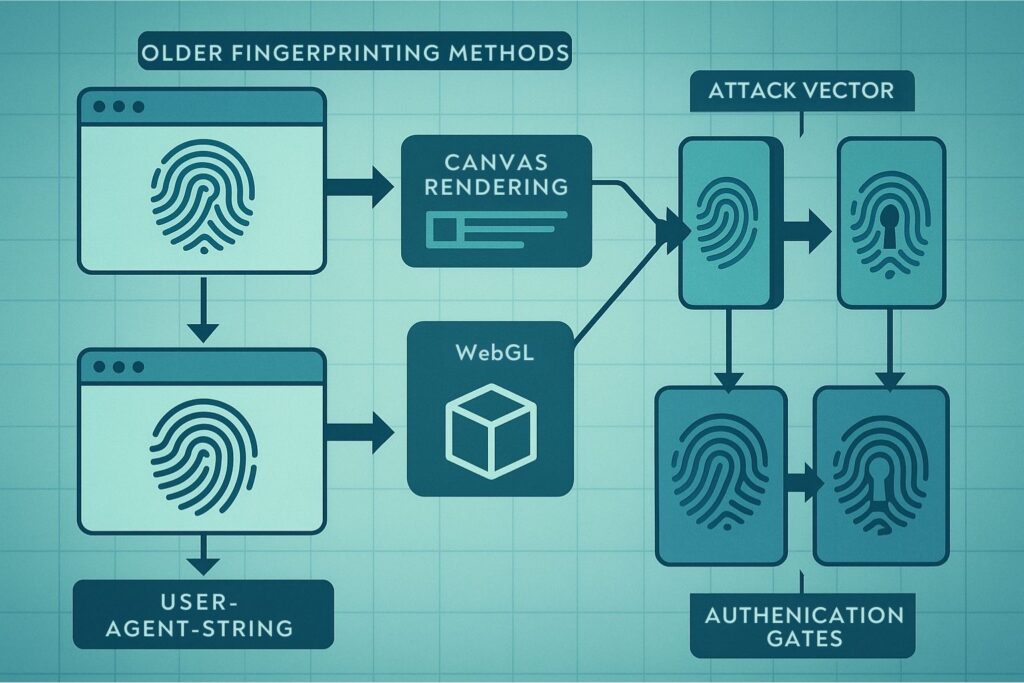

How Did Detection Used to Work? The Fingerprinting Era

For years, the game was simple: lie better than the other guy. A decade ago, detection was rudimentary. It relied on basic checks like cookies, IP reputation, and user-agent strings WebRTC. Then came the fingerprinting era. Websites started looking at a wider set of attributes to identify users: Canvas rendering, WebGL, AudioContext, and font enumeration. In response, anti-detect browsers emerged. They worked by modifying the Chromium browser to spoof these fingerprints, and for a long time, it was a successful strategy. Most tools on the market today are still optimized for that era.

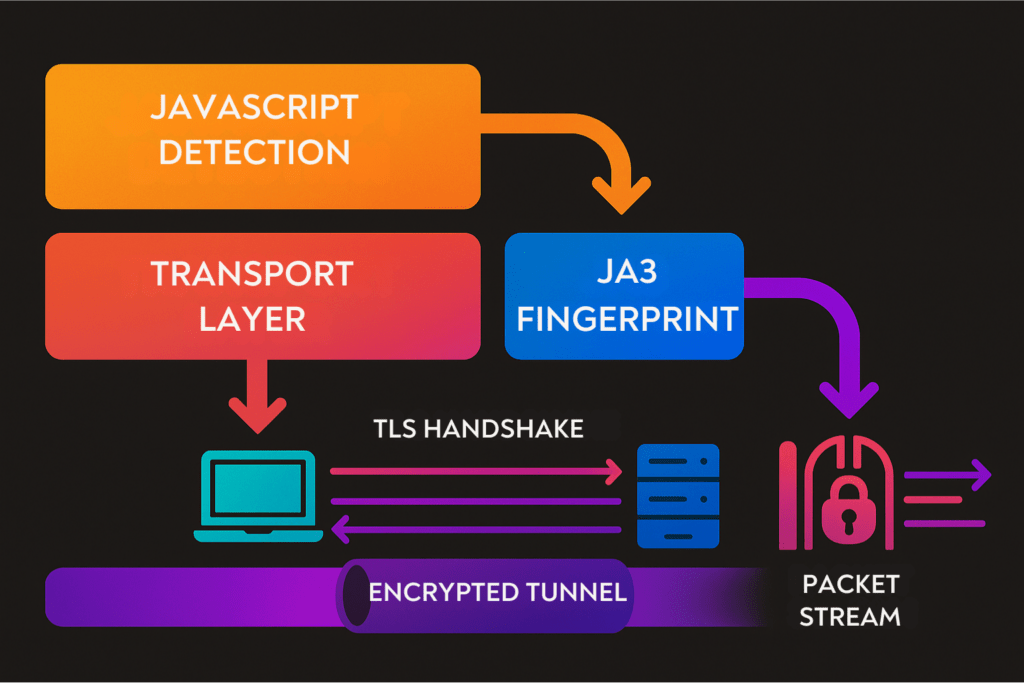

What Changed? Detection Moved Upstream

The game has changed. Detection no longer waits for JavaScript to run. Platforms now evaluate browsers before the page even loads. They’re looking at the transport layer, the very first signals your browser sends. This includes:

- TLS handshake behavior: The specific cipher suites, extensions, and their ordering create a unique signature (known as a JA3 or JA4 fingerprint).

- HTTP/2 and QUIC protocol negotiation: The way your browser communicates at the protocol level reveals its underlying engine.

- Browser build integrity: Platforms can check if your browser’s binary matches the official vendor release.

By the time your fingerprint spoofing code executes, the risk score may already be decided. An anti-detect browser can perfectly spoof a Canvas fingerprint, but if its TLS fingerprint doesn’t match that of a real Chrome browser, it’s already lost the game.

What Are the Two Philosophies for Browser Management?

This shift has led to a fork in the road, with two fundamentally different philosophies for managing browser identity. Understanding this is more important than any feature comparison.

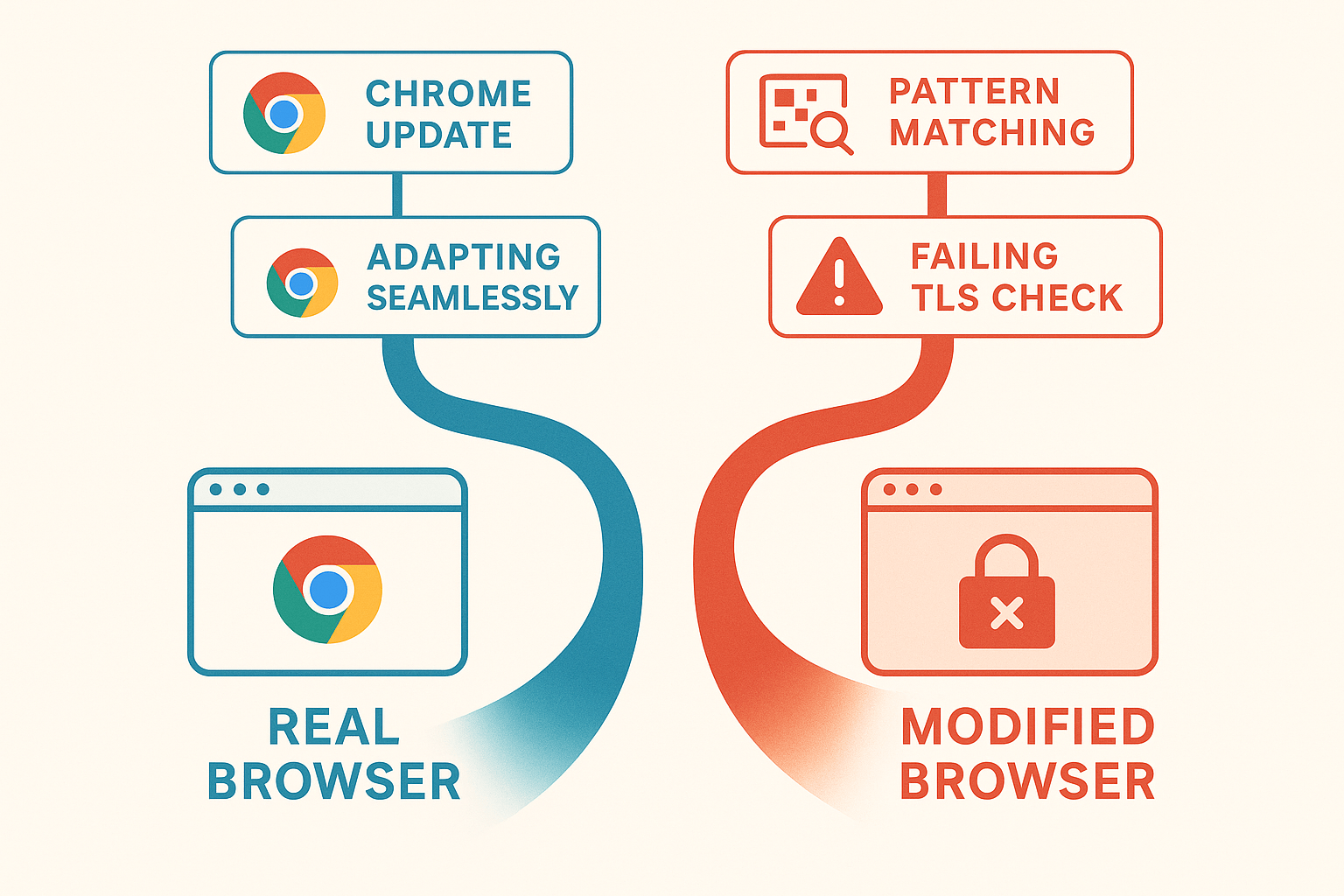

Philosophy A: Modify the Browser

This is the traditional approach. You take an open-source browser like Chromium, patch its internals to spoof fingerprints, and try to make it lie convincingly. But this approach is fraught with problems:

- The TLS fingerprint doesn’t match a real Chrome browser’s cipher suites and extensions.

- The binary hash doesn’t match vendor releases and fails code signing checks.

- The HTTP/2 protocol negotiation differs in subtle but detectable ways.

Every time Chrome updates, the gap between the modified browser and the real thing widens. It’s an arms race where one side is always playing catch-up.

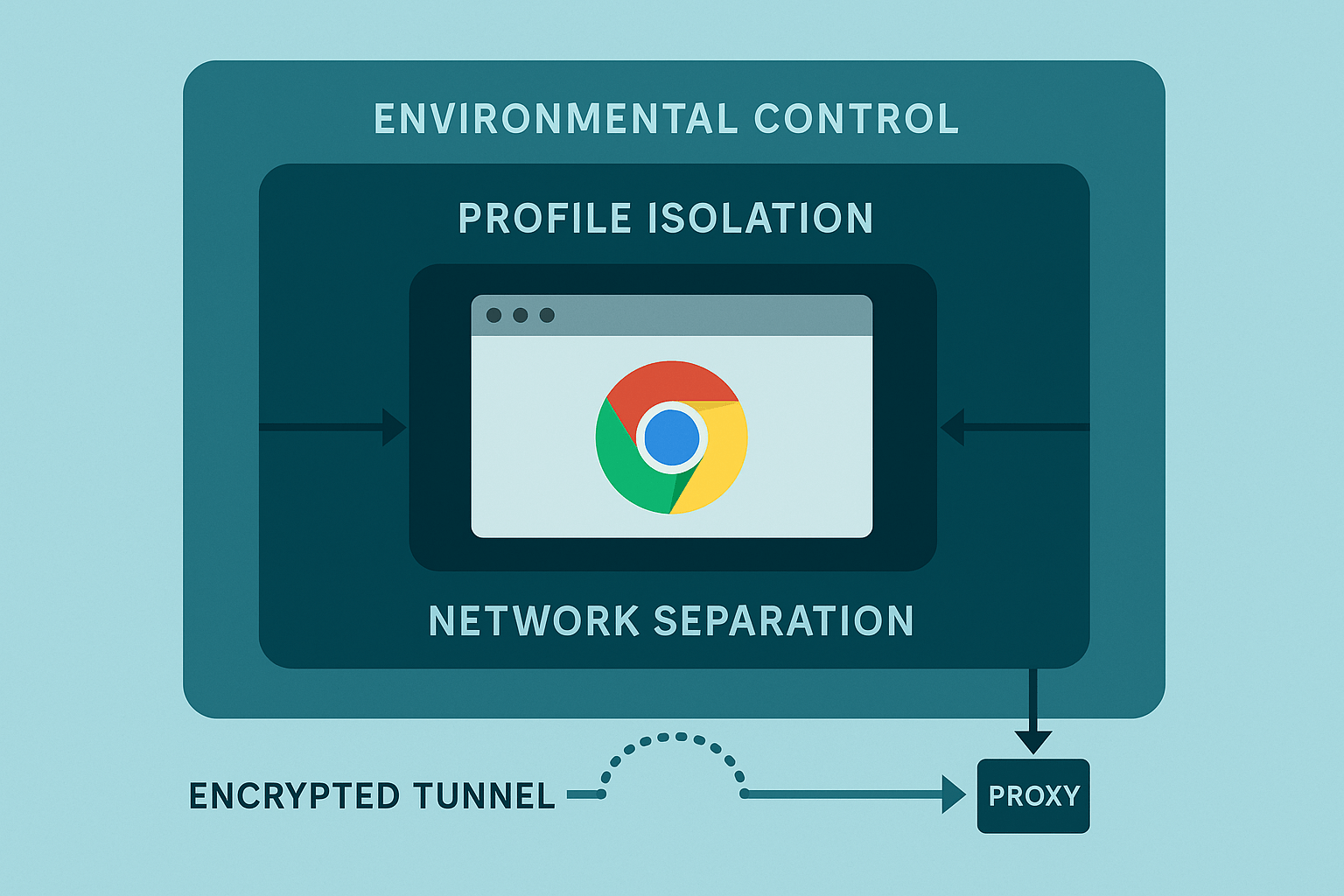

Philosophy B: Control the Environment

Instead of trying to make the browser lie, what if it never had to? This approach uses real, unmodified system browsers—the same stock Chrome, Edge, or Safari that millions of people use every day. The browser itself remains authentic and passes all integrity checks. The control comes from managing the environment around the browser:

- Profile isolation: Each identity is kept completely separate, with no shared state.

- Network separation: Each profile gets its own independent network connection.

- Environmental coherence: The timezone, locale, and other settings are aligned with the proxy’s geography.

There’s nothing to detect because nothing is fake. This is the philosophy Chameleon Mode is built on. The browser stays real. The environment creates the separation.

Why Does Randomization Backfire?

The biggest myth in this space is that more randomness equals more safety. The opposite is true. Detection systems are trained on millions of normal users. They learn what legitimate patterns look like. Real users are consistent. Their devices don’t morph, their fingerprints don’t rotate, and their entropy remains stable. Detection looks for normality, not uniqueness. Wildly randomizing your browser fingerprint is the signal. The statistical implausibility of constant change stands out. The safest identity is the one that looks boring. Consistent. Stable. Like every other real user.

What Is the Trajectory of These Two Approaches?

This is the most important takeaway. The two philosophies are on completely different trajectories.

Modified browsers are on a degrading trajectory. Every Chrome update creates a new detection surface. Every platform improvement requires new patches. The maintenance burden grows, and the gap between the modified browser and the real thing widens. The detection surface expands over time.

Real browser management is on an improving trajectory. When Chrome evolves, your browser evolves with it automatically. When TLS standards change, you inherit them natively. When platforms add new detection methods, you’re already passing because you’re using the same browser as legitimate users. The detection surface shrinks over time.

One model degrades. The other improves. This isn’t speculation—it’s the logical consequence of each architecture.

What Are the Practical Implications of This?

Your increasing burn rates aren’t just bad luck. They are a symptom of an architectural mismatch. You’re using JavaScript-era tools to fight transport-layer detection. The tool may be doing exactly what it was designed to do, but what it was designed to do is no longer enough. Chameleon Mode was built around one non-negotiable rule: the browser must always be authentic. No modified Chromium, no forked builds, no lying about the browser’s identity. Profile isolation, network separation, and environmental coherence create distinct identities while the browser passes every authenticity check. It’s not about hiding better; it’s about being correct.

Where Is This All Going?

Detection will continue to move toward trust, integrity, and consistency. Platforms are getting better at distinguishing real from imitation at unspoofable layers. The TLS handshake happens before your code runs. Binary verification happens at the OS level. These aren’t problems you can patch your way out of. The future isn’t about hiding better. It’s about alignment—working with how detection functions rather than against it. This is for anyone who wants longevity over tricks, stability over patching, and scale without playing roulette.

The most undetectable browser is not the one that lies best—it’s the one that lies the least.

People Also Ask

What is an anti-detect browser?

An anti-detect browser is a specialized web browser designed to mask a user’s digital fingerprint. It creates separate browsing environments, each with a unique set of parameters (like user agent, screen resolution, and plugins) to prevent websites from tracking the user across different accounts or sessions.

How do anti-detect browsers get detected?

Anti-detect browsers are often detected through inconsistencies in their fingerprints. For example, the browser might present a fingerprint that is statistically unlikely or doesn’t match the typical fingerprint of the browser it claims to be. Advanced detection systems can also identify them through transport-layer fingerprinting (TLS/HTTP2) and by verifying the integrity of the browser’s binary code.

Is it illegal to use an anti-detect browser?

The use of anti-detect browsers is not illegal in itself. However, their use may violate the terms of service of some websites. They can also be used for illegal activities, such as fraud or cybercrime, which is against the law.

What is the difference between a VPN and an anti-detect browser?

A VPN (Virtual Private Network) masks your IP address and encrypts your internet connection, but it does not change your browser fingerprint. An anti-detect browser, on the other hand, is designed to alter your browser fingerprint to prevent tracking, but it does not necessarily hide your IP address. For maximum privacy, they are often used together.